Diverticulosis is common...here is what you need to know

Everything essential, in under 5 minutes

Colonoscopy report: “Reassuring procedure. Diverticulosis only. Discharged to GP.”

The term sounds serious, medical and even ominous.

What does it mean? Should you be worried?

Most people with diverticulosis never know they have it.

But understanding this "wear and tear" condition of the gut can help prevent its potentially serious complications.

Below is a summary on diverticulosis, revealing what causes it and how to manage it.

What exactly is diverticulosis?

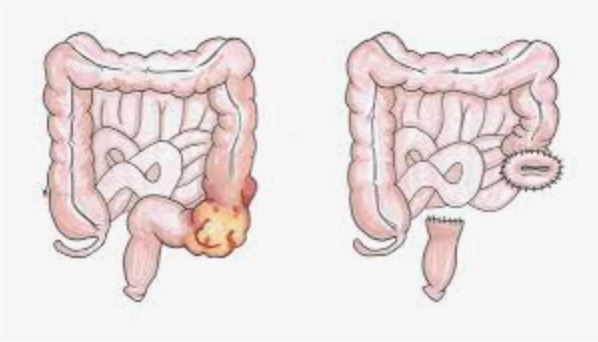

Think of diverticulosis as tiny balloon-like pouches that form along your colon wall. These pouches, called diverticula, develop when weak spots in the muscular wall, called vasa recta, which bulge outward under pressure.

When the diverticula become inflamed or infected you develop diverticulitis.

Only 5-10% of people under 40 develop diverticulosis, but prevalence jumps dramatically with each decade. By age 60, about 50% of people have diverticulosis. By 80, that number reaches 70%.

Western countries predominantly develop left-sided diverticulosis affecting the sigmoid colon (90-95% of cases), while Asian populations typically develop right-sided disease affecting the ascending colon (70-85% of cases).

The microbiome and diverticulosis

Recent research has revealed the gut microbiome plays a central role in determining who develops complications of diverticulosis.

Small studies have identified specific bacteria may be associated with diverticulitis. One study showed people with active inflammation had enrichment of harmful bacteria like Ruminococcus gnavus and Clostridium species, while beneficial bacteria like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Eubacterium eligens became depleted.

Looking at the other studies the results are heterogeneous (mixed) therefore there is likely an association rather than causation….larger studies needed! It is plausible that microbiome disruption (dysbiosis) leads to inflammatory compound release, weakening the colon barrier leading to diverticulitis.

Medications that increase your risk

NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) increase the risk of diverticulitis and diverticular related bleeding. NSAIDs reduce protective prostaglandins, thin the intestinal mucus layer, and increase gut permeability.

Opioids present another major risk. They slow gut motility, increase constipation, and alter immune responses. Studies show opioid users face higher rates of bleeding, perforation, and sepsis when diverticulitis develops.

Corticosteroids increase perforation risk by suppressing immune responses and impairing tissue healing. Even short courses can be problematic in vulnerable patients.

The great fibre debate

In western countries, the lack of dietary fibre may be associated with the development of diverticulosis. The proposed mechanism is low fibre intake reduces stool bulk and increases transit time, generating higher intra-luminal pressures through exaggerated segmental contractions. This mechanical stress, repeated over decades, may gradually weaken the colonic wall. Fibre emerges as a protective force; individuals consuming 30g daily show 41% reduced risk compared to those with minimal intake

The traditional "pressure theory" has been challenged. Some studies found no relationship between fibre intake and diverticulosis development. However, large meta-analyses consistently show fibre reduces diverticulitis risk by 23-58% depending on intake levels.

Cereal fibre and fruit fibre provide the strongest protection, while vegetable fibre shows less benefit (that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t eat your vegetables!). Insoluble fiber appears more protective than soluble fibre.

Individual microbiome composition possibly determines fibre's effectiveness. In a nature article people with adequate levels of beneficial bacteria like Bacteroides uniformis respond better to fibre supplementation.

Understanding your risk: the DICA score

The Diverticular Inflammation and Complication Assessment (DICA) score helps predict who's most likely to develop problems. This validated system examines:

Number of diverticula: More than 15 per bowel segment increases risk

Location: Involvement of multiple bowel segments

Inflammation markers: Signs of ongoing irritation

Complications: Presence of narrowing, bleeding, or pus

DICA categories translate to clear risk levels:

DICA 1 (low risk): 3% chance of developing diverticulitis over 3 years

DICA 2 (moderate risk): 12% chance of problems

DICA 3 (high risk): 22% chance of complications

When asymptomatic becomes symptomatic

80% of people with diverticulosis remain asymptomatic forever. Their diverticula cause no symptoms, require no treatment, and present no dangers.

About 20% develop symptoms at some point, persistent abdominal pain, bowel habit changes, or bloating. This condition, called Symptomatic Uncomplicated Diverticular Disease (SUDD), resembles irritable bowel syndrome but stems from low-grade inflammation around diverticula.

Only 5-10% progress to diverticulitis - Inflammation within the diverticula themselves. This presents with left lower quadrant abdominal pain, fever, elevated white blood cell count, and CT scan evidence of infection.

Complications affect 15-25% of diverticulitis cases. These include abscess formation (11% of hospitalised cases), perforation (1%), bleeding (0.5%), and fistula formation (14% after an acute episode).

Antibiotics - yay or nay?

Historically, Acute uncomplicated diverticulitis required antibiotic therapy targeting gram-negative organisms and anaerobes (metronidazole, ciprofloxacin or co-amoxiclav)

However, one of the most significant recent changes involves antibiotic use.

Routine antibiotics are no longer recommended for uncomplicated diverticulitis in healthy patients.

Major trials like DIABOLO and AVOD showed no benefit from antibiotics in mild cases. Patients recovered equally well whether they received antibiotics or not.

This represents a fundamental shift from previous aggressive antibiotic protocols.

Antibiotics remain important for specific situations:

Immunocompromised patients

Complicated diverticulitis with abscess or perforation

High-risk patients with severe symptoms

Failure to improve with conservative management

Probiotic limitations

Emerging research suggests specific probiotic strains may help manage diverticular disease. Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC PTA 4659 showed some benefits in SUDD. An RCT reported the supplementation with L. reuteri 4659 together with bowel rest and fluids significantly reduced both blood and faecal inflammatory markers compared to the placebo group.

However, there is no strong evidence to support probiotics for primary prevention of diverticulitis.

The probiotic field suffers from significant quality control issues. Many commercial products contain different strains or quantities than listed on labels. Until better evidence emerges, probiotics should be considered experimental rather than standard therapy.

Foods that protect, foods that harm

Recent research has demolished several dietary myths while confirming others.

Nuts, seeds, and popcorn are NOT harmful. This decades-old advice has been thoroughly de-bunked. Multiple large studies show these foods pose no increased risk and may actually be protective due to their fibre content.

Protective foods include:

Whole grains (quinoa, brown rice, oats)

Fruits with skin (apples, berries, pears)

Vegetables (leafy greens, broccoli, carrots)

Legumes (beans, lentils, chickpeas)

Nuts and seeds (previously forbidden)

Mediterranean dietary patterns show promise, emphasizing anti-inflammatory foods like olive oil, fish, fruits, and vegetables while limiting red meat and processed foods.

Red meat limitation appears beneficial. Studies suggest keeping red meat consumption below 12-16 ounces monthly may reduce diverticulitis risk.

When surgery becomes necessary

Surgical thinking has evolved dramatically. The old "two-strike rule" (surgery after two episodes) has been abandoned in favour of individualised decision-making.

Emergency surgery indications include:

Perforation with peritonitis

Large abscesses (>4-5cm) not responding to drainage

Haemodynamic instability

Failed conservative management

Elective surgery considerations:

Recurrent episodes significantly affecting quality of life

Complicated disease (fistula, obstruction, stricture)

Immunocompromised status

Patient preference after thorough counselling

Surgical outcomes vary significantly. Emergency surgery carries 10.6% mortality, while elective surgery has 0.5% mortality. However, 25% of patients experience persistent symptoms after surgery, highlighting the importance of careful patient selection.

Practical prevention strategies

Primary prevention focuses on lifestyle:

Aim for 25-30 grams of daily fibre, gradually increasing by 5 grams weekly

Maintain regular exercise, emphasising vigorous activity when possible (there may be some benefits in preventing diverticulitis)

Stay well-hydrated (no brainer and general rule of life)

Maintain healthy weight (BMI <30)

Avoid smoking and limit alcohol

Use NSAIDs cautiously, especially long-term

Secondary prevention for people with known diverticulosis includes the same lifestyle measures plus awareness of warning signs requiring medical attention.

The future of diverticulosis care

Research continues to re-shape our understanding. Personalised medicine approaches based on microbiome analysis may soon guide treatment decisions. Targeted dietary interventions tailored to individual bacterial profiles show promise.

Microbiome-based therapies are under development, including specific probiotic cocktails and even faecal microbiota transplantation for severe cases.

However, these are currently research gaps.

Key takeaways…

Diverticulosis represents a common condition of aging that usually remains silent. When symptoms develop, modern management emphasises lifestyle interventions over aggressive medical treatment.

The most important actions you can take:

Embrace a high-fibre diet with whole grains, fruits, and vegetables

Exercise regularly, emphasising vigorous activity when possible

Maintain healthy body weight

Use medications like NSAIDs judiciously

Don't fear nuts, seeds, or popcorn

Recognise warning signs requiring immediate medical attention: severe abdominal pain, fever, persistent vomiting, or blood in stool.

Understanding diverticulosis empowers you to take control of your digestive health. With proper lifestyle choices, most people can prevent complications and maintain excellent quality of life despite having this common condition.

The microbiome revolution in diverticulosis research offers hope for more targeted, personalised treatments. Until then, the fundamentals remain powerful: eat well, move regularly, and listen to your body.

Struggling with digestive issues that affect your daily life? Invest in your gut health with a private, personalised consultation where I will explore your specific symptoms and develop a targeted treatment plan. Take the first step toward digestive wellness today: https://bucksgastroenterology.co.uk/contact/

References

Williams S et al. Diverticular disease: update on pathophysiology, classification and management. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2023 Jul 27;15(1):50-58

Hawkins AT et al. Diverticulitis: An Update From the Age Old Paradigm. Curr Probl Surg. 2020 Oct;57(10):100862

https://radiologykey.com/diverticular-disease-of-the-colon/

Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009 Aug;22(3):141-6.

Fugazzola, P et al. The WSES/SICG/ACOI/SICUT/AcEMC/SIFIPAC guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute left colonic diverticulitis in the elderly. World J Emerg Surg 17, 5 (2022).

Imaeda H, Hibi T. The Burden of Diverticular Disease and Its Complications: West versus East. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2018 Dec;3(2):61-68

Ma W et al. Gut microbiome composition and metabolic activity in women with diverticulitis. Nat Commun. 2024 Apr 29;15(1):3612

Strate LL, Morris AM. Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Treatment of Diverticulitis. Gastroenterology. 2019 Apr;156(5):1282-1298.e1.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459316/

Peery AF et al. A high-fiber diet does not protect against asymptomatic diverticulosis. Gastroenterology. 2012 Feb;142(2):266-72.e1

Aune D, Sen A, Norat T, Riboli E. Dietary fibre intake and the risk of diverticular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Nutr. 2020 Mar;59(2):421-432

Mohamedahmed AY et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the management of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis: time to change traditional practice. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2024 Apr 5;39(1):47.

Ojetti V et al. Randomized control trial on the efficacy of Limosilactobacillus reuteri ATCC PTA 4659 in reducing inflammatory markers in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 May 1;34(5):496-502

I was convinced my diverticulitis episode (presenting right) was due to the pain meds and opiates taken due to/ during my abortion, I'm finally reading something that makes me feel like I was not imagining things despite doc telling me it was due to a low fibers diet (which isn't my case).

Comprehensive article. The nuts urban legend. 🤣 No body believes there doctor these days.