What is Barrett's Oesophagus?

If you have persistent reflux….you may want to read this!

“Your gastroscopy showed something called Barrett’s oesophagus,” I explain gently.

“You’ll need surveillance.”

Mrs T looks at me, confused. “Surveillance? Like…being watched?”

I smile. “Regular check-ups. To keep you safe.”

She nods, but I can see the worry.

The word surveillance carries weight. It suggests something lurking. Something that needs monitoring.

This article is for Mrs T. And for anyone else who’s received a Barrett’s diagnosis and left the clinic with more questions than answers.

Let’s make sense of it together.

Disclaimer: Barrett’s oesophagus is a nuanced condition. The management depends on segment length, presence of dysplasia (high risk features), your other health conditions, and factors unique to you. What follows is general information to help you understand the condition….not a personal treatment plan. For your specific management, please speak to your gastroenterologist or specialist. They know your case. I don’t.

A brief history

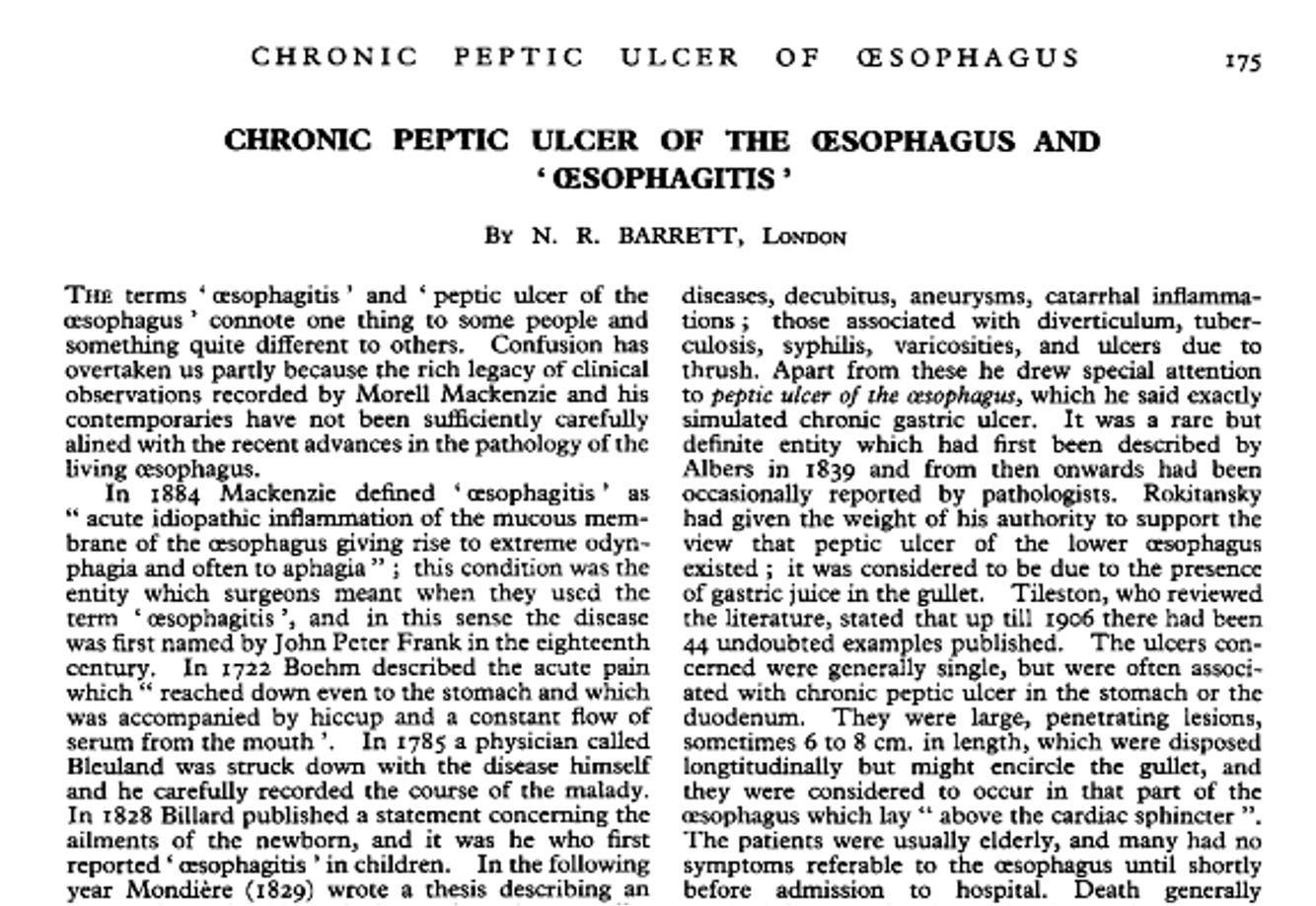

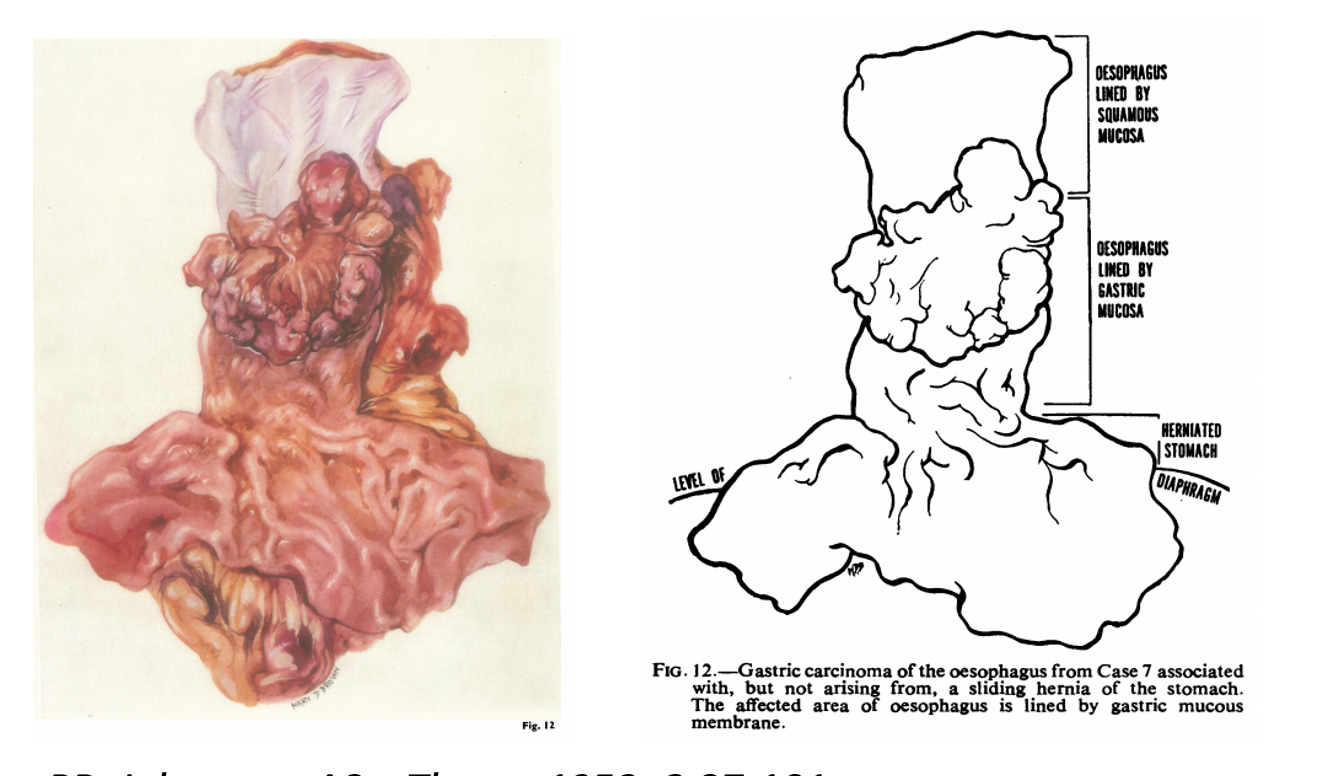

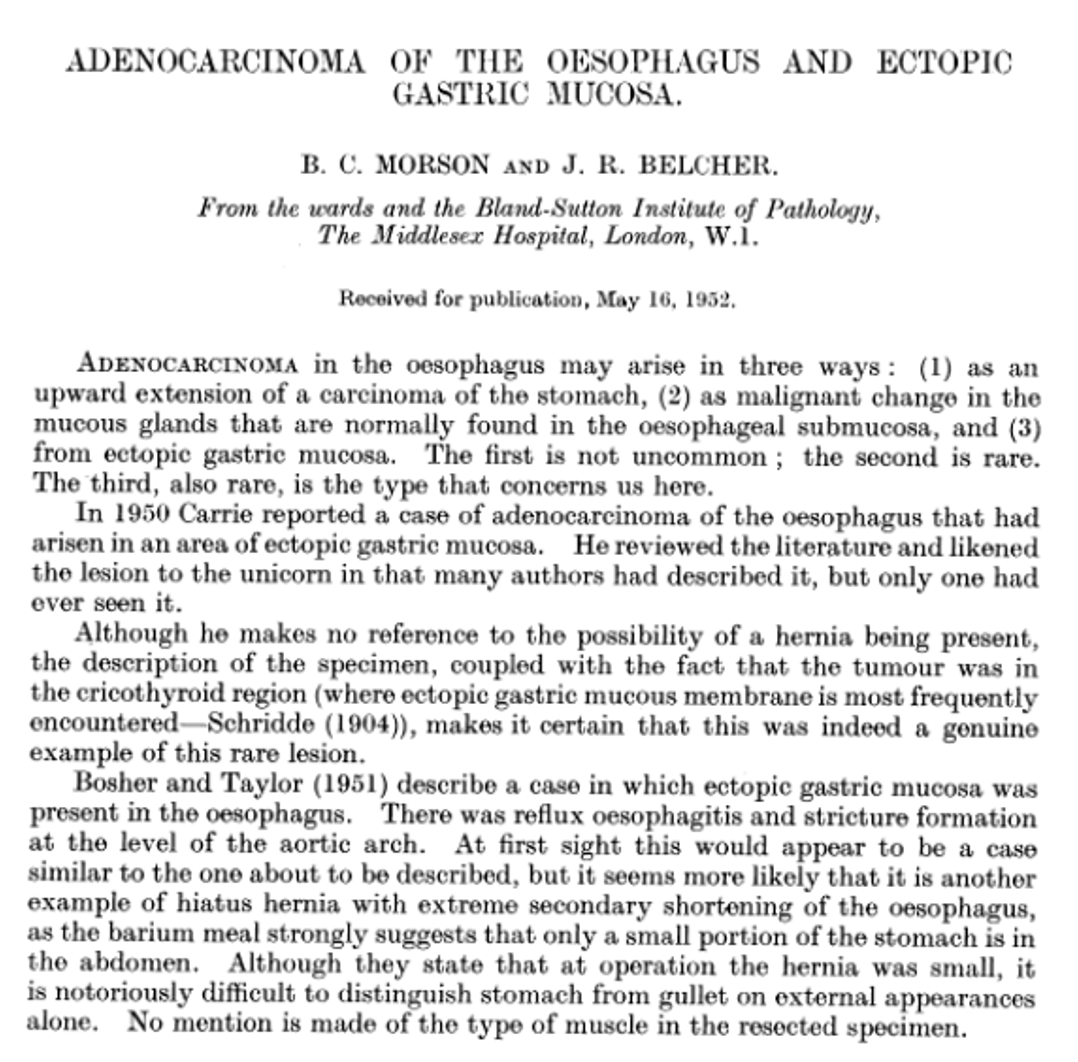

The condition bears the name of Norman Barrett, an Australian-born British surgeon working at St Thomas’ Hospital in London. In 1950, he published a paper describing an unusual finding: columnar epithelium (intestine-like cells) lining the lower oesophagus.

Although he’s a legend…..Barrett got it wrong, but he got the ball rolling.

He believed this was a congenital abnormality….a stomach that had crept upwards. It took other researchers, Philip Allison and Alan Johnstone, to prove in 1953 that this was actually the oesophagus itself….transformed.

Barrett graciously accepted the correction. But the name stuck (phew).

By 1975, we understood something more concerning. A landmark study by Naef and colleagues followed 140 patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Twelve developed oesophageal adenocarcinoma. The cancer link was established.

And surveillance began.

What actually happens

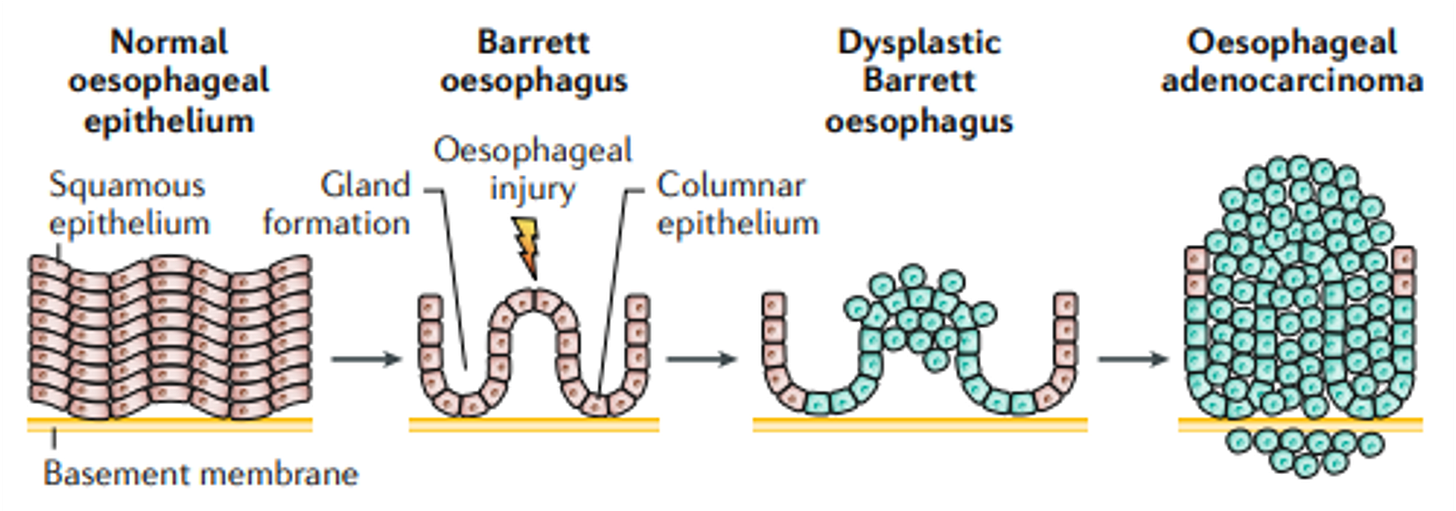

Your oesophagus is lined with flat, layered cells called squamous epithelium.

When stomach acid repeatedly washes upward, these cells take a beating. They’re not designed for chronic acid exposure.

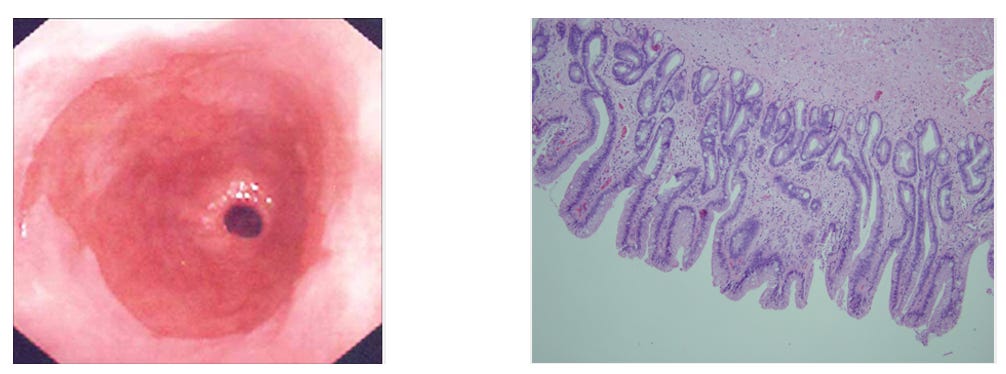

The vulnerable squamous cells transform into taller, column-shaped cells resembling those in your intestine. This process is called intestinal metaplasia. Under an endoscope, it looks salmon-pink and velvety, quite distinct from the pale oesophageal lining above.

Think of it as your body’s attempt at self-protection. The intestine deals with acid and digestive enzymes daily….so intestinal-type cells have better defences. Your oesophagus is essentially reprogramming itself to survive.

The problem? This transformation carries a small but real risk.

These changed cells can, over many years, develop further abnormalities. The sequence runs: normal cells → metaplasia (Barrett’s) → dysplasia (pre-cancerous changes) → adenocarcinoma.

Before you panic….let me put this in perspective.

Only 1-2 in 100 people with Barrett’s oesophagus will ever develop cancer. The vast majority, will not.

But that small risk is why we watch. And watching works.

Who’s at risk?

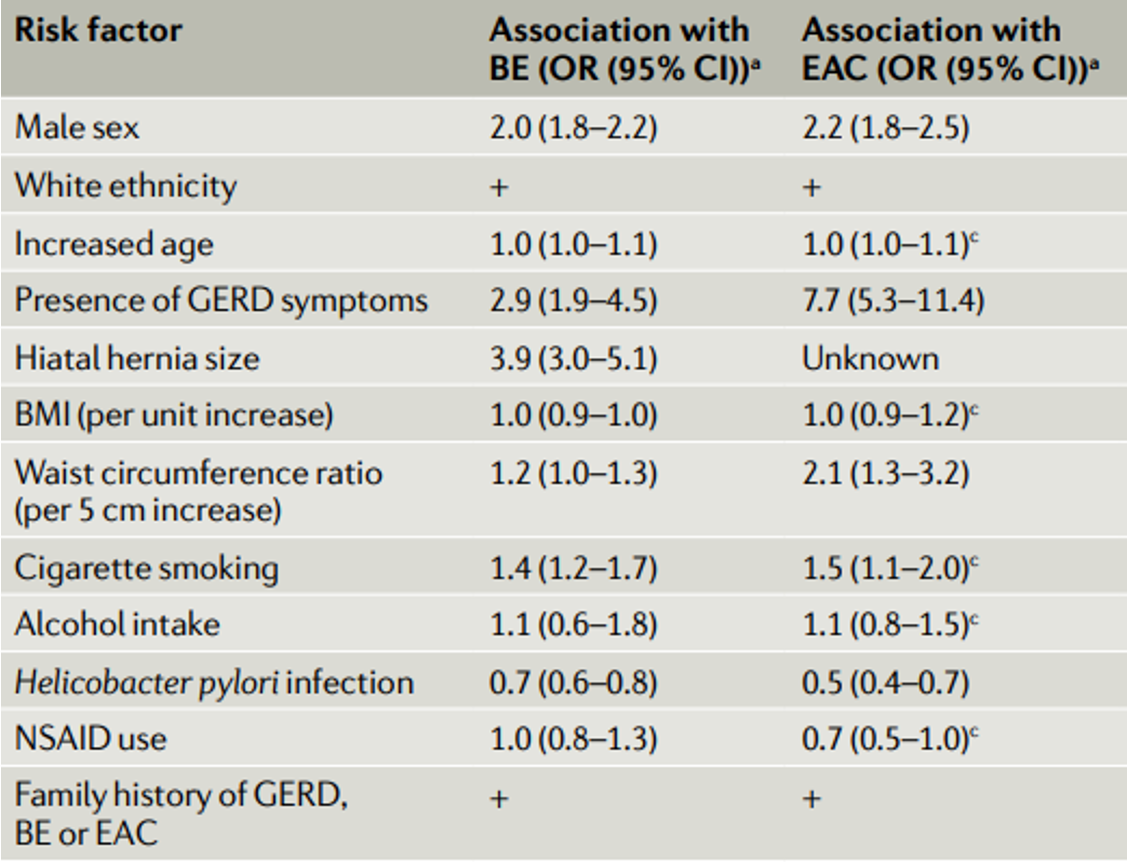

Barrett’s doesn’t happen overnight. It takes years. Sometimes decades.

Chronic reflux is the biggest driver. Studies show that people with reflux symptoms lasting more than 20 years have a five to six-fold increased risk. If you’ve had heartburn since your twenties, you’re at higher risk than someone whose symptoms started last year….even if theirs feel worse.

Being male doubles your risk. The ratio is roughly 2:1, rising to 4:1 in those under 50. We don’t fully understand why, though central fat distribution and hormonal differences likely play a role. Women tend to develop Barrett’s about 20 years later than men.

Carrying excess weight, particularly around your middle, increases risk significantly. A high waist-to-hip ratio more than doubles your odds. Every five centimetres added to your waist circumference nudges risk upward. Visceral fat creates mechanical pressure on the stomach and promotes inflammation….a double burden.

Smokers have roughly 1.7 times the risk of non-smokers. The effect persists even after quitting, particularly in those with heavy past use.

A hiatus hernia deserves special mention. Nearly all Barrett’s patients (96% in one study) have a hiatus hernia of at least 2cm. The hernia creates a reservoir where acid pools, then splashes upward. It weakens the lower oesophageal sphincter and delays acid clearance.

If you have a first-degree relative with Barrett’s or oesophageal cancer, your risk increases substantially. Family history suggests either shared genetics, shared environment, or both.

And ethnicity plays a role. Barrett’s is more common in Caucasian populations. Rates are lower in Black and Asian communities, though the reasons remain unclear.

What we look for during gastroscopy

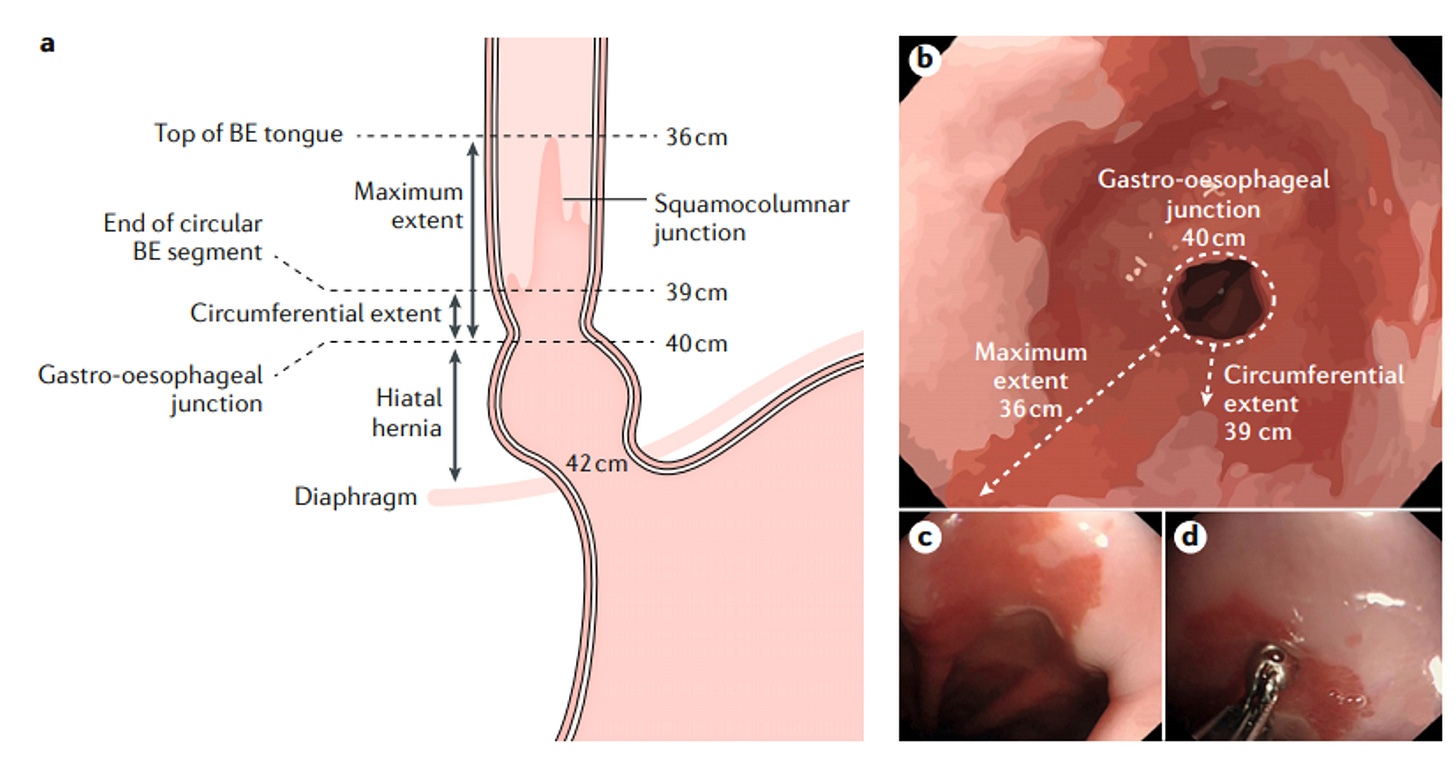

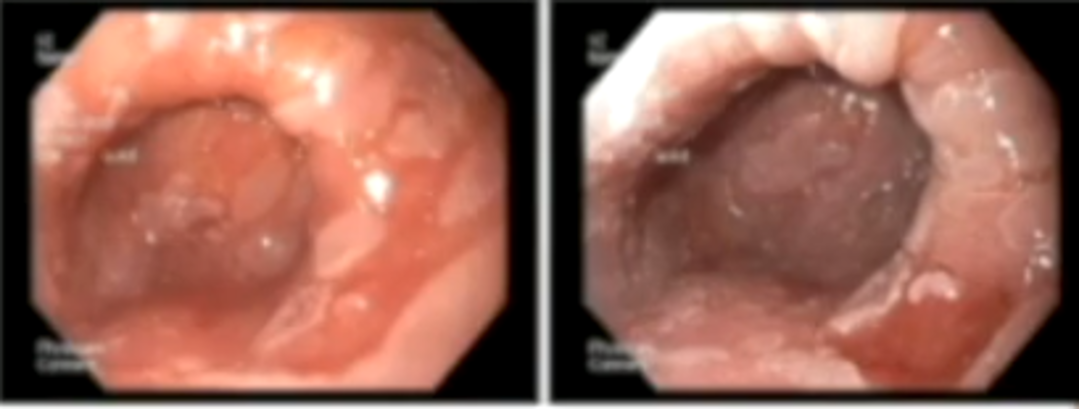

When I perform a gastroscopy on someone with suspected Barrett’s, I’m looking for that characteristic salmon-pink mucosa extending up from where the oesophagus meets the stomach.

We measure it using the Prague classification. Two letters: C and M.

C stands for circumferential extent….how far the Barrett’s tissue extends around the entire circumference. M stands for maximum extent….the longest tongue or projection, even if it doesn’t go all the way around.

So C2M5 means 2cm of circumferential Barrett’s, with the longest tongue reaching 5cm. Simple but important, because length correlates with cancer risk. Every additional centimetre increases your risk by about 21%.

Short-segment Barrett’s is less than 3cm. Long-segment is 3cm or more.

But the real question isn’t just “how much Barrett’s?”

It’s “is there dysplasia?”

Dysplasia means pre-cancerous cellular changes. The cells look abnormal under the microscope, but they haven’t yet invaded deeper tissues. We classify it as low-grade or high-grade.

This is what surveillance is really hunting for. Catch dysplasia early, treat it, and you’ve interrupted the progression to cancer.

To find it, we follow the Seattle protocol: four biopsies taken at every 2cm throughout the Barrett’s segment, plus targeted biopsies of anything that looks suspicious. It’s meticulous work. But thoroughness saves lives.

Modern endoscopes help. Narrow band imaging highlights subtle abnormalities. Spraying acetic acid (essentially vinegar) onto the tissue makes dysplastic areas stand out. These techniques increase our detection rate significantly.

Treatment and management

Let’s start with what you can control.

Lifestyle modifications genuinely help. I’ve written extensively about this in my recent article on reflux management, but the essentials bear repeating: sleep on your left side, elevate the head of your bed, stop eating three hours before bed, keep portions reasonable, and if you smoke….stop.

Weight loss, if you’re carrying excess weight, reduces reflux episodes dramatically. One study showed 80% of participants had symptom reduction after losing an average of 13kg, with 65% achieving complete resolution.

But for Barrett’s, lifestyle alone isn’t enough.

Long-term acid suppression forms the cornerstone of treatment. This typically means a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) like omeprazole, lansoprazole, or esomeprazole.

The AspECT trial, published in The Lancet in 2018, changed how we think about this. This landmark randomised controlled trial followed over 2,500 Barrett’s patients for nearly nine years. High-dose PPI (esomeprazole 40mg twice daily) significantly reduced the risk of death, cancer, or high-grade dysplasia compared to low-dose treatment.

The numbers: if the expected time to a bad outcome was 8 years on low-dose PPI, high-dose extended that to over 10 years. All-cause mortality dropped. The combination of high-dose PPI plus aspirin showed the strongest protective effect.

We’re treating the underlying condition. High-dose, long-term.

A word on long-term PPI use. You may have heard concerns. Let me address them directly.

Magnesium levels can drop with prolonged PPI use….the drug affects intestinal absorption. If you’re on a PPI long-term, consider supplementing magnesium (magnesium glycinate works well) and mention it to your doctor so they can check levels if needed.

Bone health deserves attention too. Some studies suggest a modest increase in fracture risk with long-term PPIs, though the evidence quality is mixed. Ensure adequate calcium and vitamin D intake. Discuss bone density screening if you have other risk factors.

For Barrett’s patients specifically, the benefits of high-dose PPI therapy, a significant reduction in mortality and cancer risk, almost certainly outweigh these potential concerns. But stay informed. Monitor. Adjust as needed.

When we find dysplasia, treatment intensifies.

Low-grade dysplasia, confirmed by two expert pathologists at two separate endoscopies, may warrant radiofrequency ablation (RFA). This technique uses controlled heat to destroy the abnormal tissue. Success rates are excellent….80-90% achieve complete remission.

High-grade dysplasia or early cancer requires more aggressive intervention. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) physically removes visible lesions. RFA then treats the remaining Barrett’s tissue.

The UK National HALO Registry, tracking patients for over 10 years, shows cancer progression in fewer than 5% after successful ablation. That’s a dramatic reduction in risk.

These are highly specialised procedures. If your surveillance identifies concerning changes, you’ll be referred to a centre with expertise in Barrett’s management.

What surveillance looks like

If you have Barrett’s oesophagus without dysplasia, NICE guidelines (updated in 2023) recommend:

For long-segment Barrett’s (3cm or more): gastroscopy every 2-3 years.

For short-segment Barrett’s with intestinal metaplasia: every 3-5 years.

For short-segment Barrett’s without intestinal metaplasia: you may not need ongoing surveillance at all, after two confirmatory endoscopies.

If low-grade dysplasia is found and confirmed, treatment with RFA is typically offered. High-grade dysplasia prompts more urgent intervention.

The intervals might seem long. But remember: Barrett’s progresses slowly. Years to decades. Regular surveillance catches problems while they’re still treatable.

Final thoughts

A Barrett’s diagnosis can feel frightening. The word surveillance conjures images of something sinister being watched.

But here’s another way to see it.

Surveillance is protection. It’s your medical team keeping careful watch so that if anything changes, we catch it early. And early intervention works.

Most people with Barrett’s will never develop cancer. Those who do develop dysplasia have excellent treatment options. The journey from normal oesophagus to Barrett’s to cancer takes many years….plenty of time for us to intervene.

So take your PPI. Make those lifestyle changes. Show up for your surveillance appointments.

And live your life.

Your oesophagus has already shown remarkable adaptability. With proper care, it will serve you well for decades to come.

Struggling with liver or digestive issues that affect your daily life? Invest in your gut health with a private, personalised consultation where I will explore your specific symptoms and develop a targeted treatment plan. Take the first step toward digestive wellness today: https://bucksgastroenterology.co.uk/contact/ (I offer both in person and video consultations!)

References

Barrett NR. Chronic peptic ulcer of the oesophagus and ‘oesophagitis’. Br J Surg. 1950;38(150):175-82.

Allison PR, Johnstone AS. The oesophagus lined with gastric mucous membrane. Thorax. 1953;8(2):87-101.

Naef AP, Savary M, Ozzello L. Columnar-lined lower esophagus: an acquired lesion with malignant predisposition. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1975;70(5):826-35.

Jankowski JAZ, et al. Esomeprazole and aspirin in Barrett’s oesophagus (AspECT): a randomised factorial trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10145):400-408.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Barrett’s oesophagus and stage 1 oesophageal adenocarcinoma: monitoring and management (NG231). February 2023.

Shaheen NJ, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(4):559-587.

Singh S, et al. Central adiposity is associated with increased risk of esophageal inflammation, metaplasia, and adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(11):1399-1412.

Hvid-Jensen F, et al. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(15):1375-83.

Sharma P, et al. The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for Barrett’s esophagus: the Prague C & M criteria. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(5):1392-9.

Haidry RJ, et al. Radiofrequency ablation and endoscopic mucosal resection for dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus and early esophageal adenocarcinoma: outcomes of the UK National Halo RFA Registry. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):87-95.

General Disclaimer

Please note that the opinions expressed here are those of Dr Hussenbux and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust. The advice is intended as general and should not be interpreted as personal clinical advice. If you have problems, please tell your healthcare professional, who will be able to help you.

Fascinating! Thanks again. Your posts are doing a great service to us all.

Nicely done. Very comprehensive. I've done my share of Barrett's surveillance over the years, and the yield for significant findings are quite well. I think the net we are using is too wide, as is often the case in our profession.